A Player’s Ceiling

The discourse surrounding a player’s “ceiling” has seen a resurgence yet much of this conversation is rooted in a reductive premise: the idea that a player’s potential is directly proportional to how frequently they end rallies with their own hand—whether through winners or unforced errors. This narrative tends to favor those who play with relentless aggression, often mistaking intent for outcome.

At first glance, the line of reasoning appears logical. However, tennis, much like football, is a percentage-based game. In football, the concept of expected goals (xG) is used to assess the quality of a scoring opportunity. Tennis, too, has its analog—let’s call it xShot: the likelihood that a particular shot, executed from a specific position with a specific shot type, moves the player closer to winning the point.

Crucially, “winning the point” does not always require a clean winner. More often, it’s a gradual, probabilistic process—each shot incrementally shifting the rally’s dynamic, nudging the odds in one’s favor. This encompasses everything from spatial awareness to anticipatory judgment, from subtle court positioning to the orchestration of cumulative pressure. In this context, we might imagine a metric akin to post-hit xShot—an analog to football’s post-strike xG—where the value of a shot is assessed not as a discrete variable, but in terms of its continuous impact on the opponent’s options.

The fixation on outright winners obscures a more nuanced narrative. Many points that culminate in forced errors are, in fact, the result of deliberate construction: rallies built with discipline and foresight, yet rendered less salient in the eye test by the fact that the final touch comes from the opponent’s racquet.

Aggressive players often dominate discussions of a “ceiling.” Yet Sloane Stephens’ 2017 US Open run illustrates “unplayability” in another dimension: her brilliance lay not in unrelenting assault (though her aggressive inside-out forehands, undeniably the shot of the tournament, certainly rose to the occasion), but in the composed resilience to absorb pressure, recalibrate strategy, and quietly seize control. She elevated her “xShot” not with an attempt of a barrage of winners, but through decentralized highs with moments of normalized defense and negative transitions, which constitute an equally formidable ceiling.

It brings to mind the familiar Christian prayer:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

The courage to change the things I can,

And the wisdom to know the difference.

While there will always be countless praise in a player’s ability to dictate, less attention is given to the discernment required to know when not to.

Vika the Victim

One of the reasons I created the @OptaLena account was an urge to “do it right” after spotting a factual error during Stuttgart last year—an issue that felt emblematic of various problems in how Opta structures and presents its data.

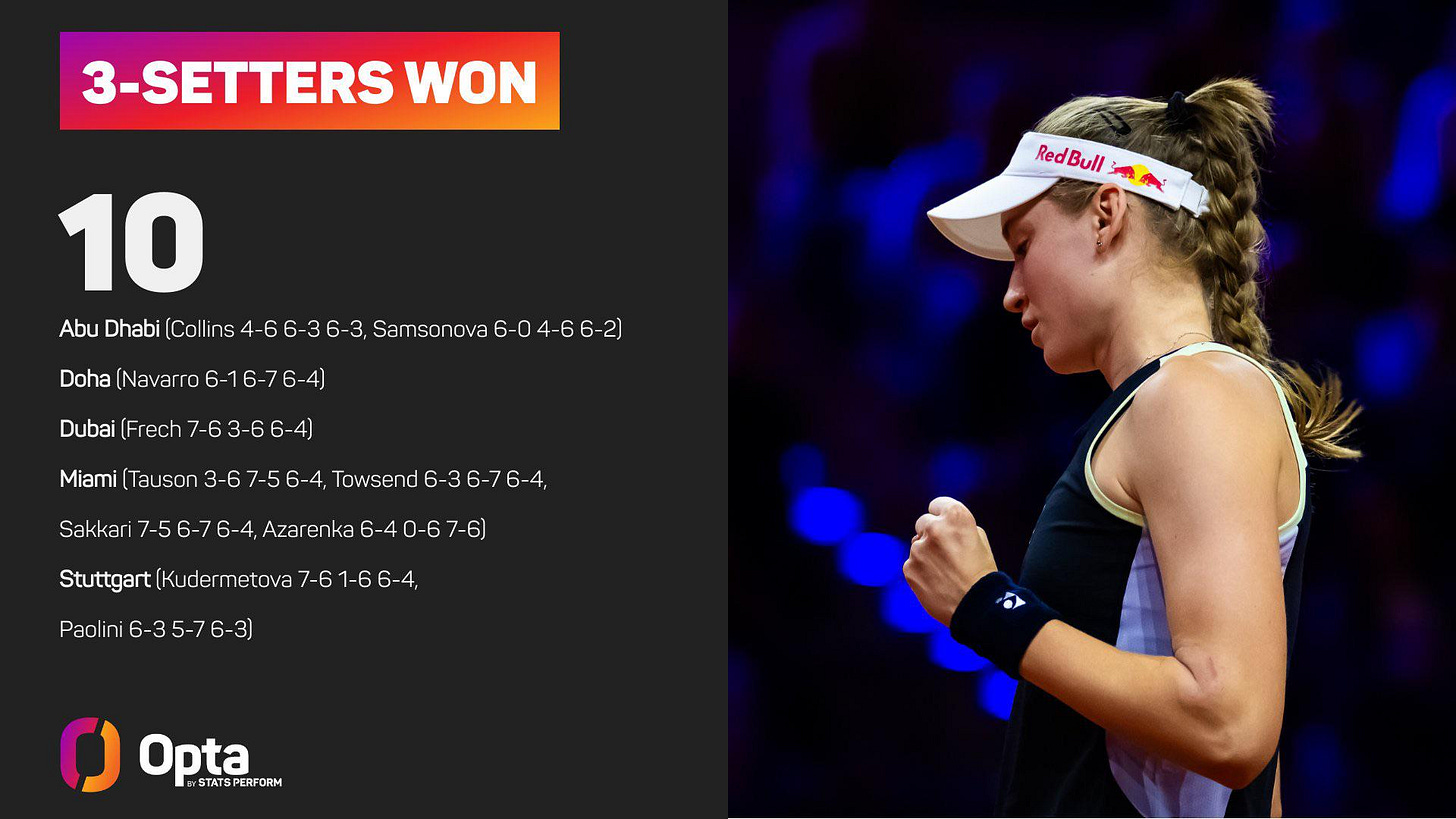

At the time, Opta claimed that Elena Rybakina was the first player since Naomi Osaka (2019–2020) to win ten consecutive three-set Tour-level matches. But this simply wasn’t the case. The actual title belongs to Zheng Qinwen who achieved the feat from the 2023 US Open through to the 2024 Australian Open. Even if one were to disregard her wins at the now-defunct 2023 Elite Trophy—though it was a sanctioned WTA event—Zheng still held an uninterrupted streak stretching to the 2024 Miami Open. This is not a complicated error to avoid. A basic database filter would have surfaced the correct player.

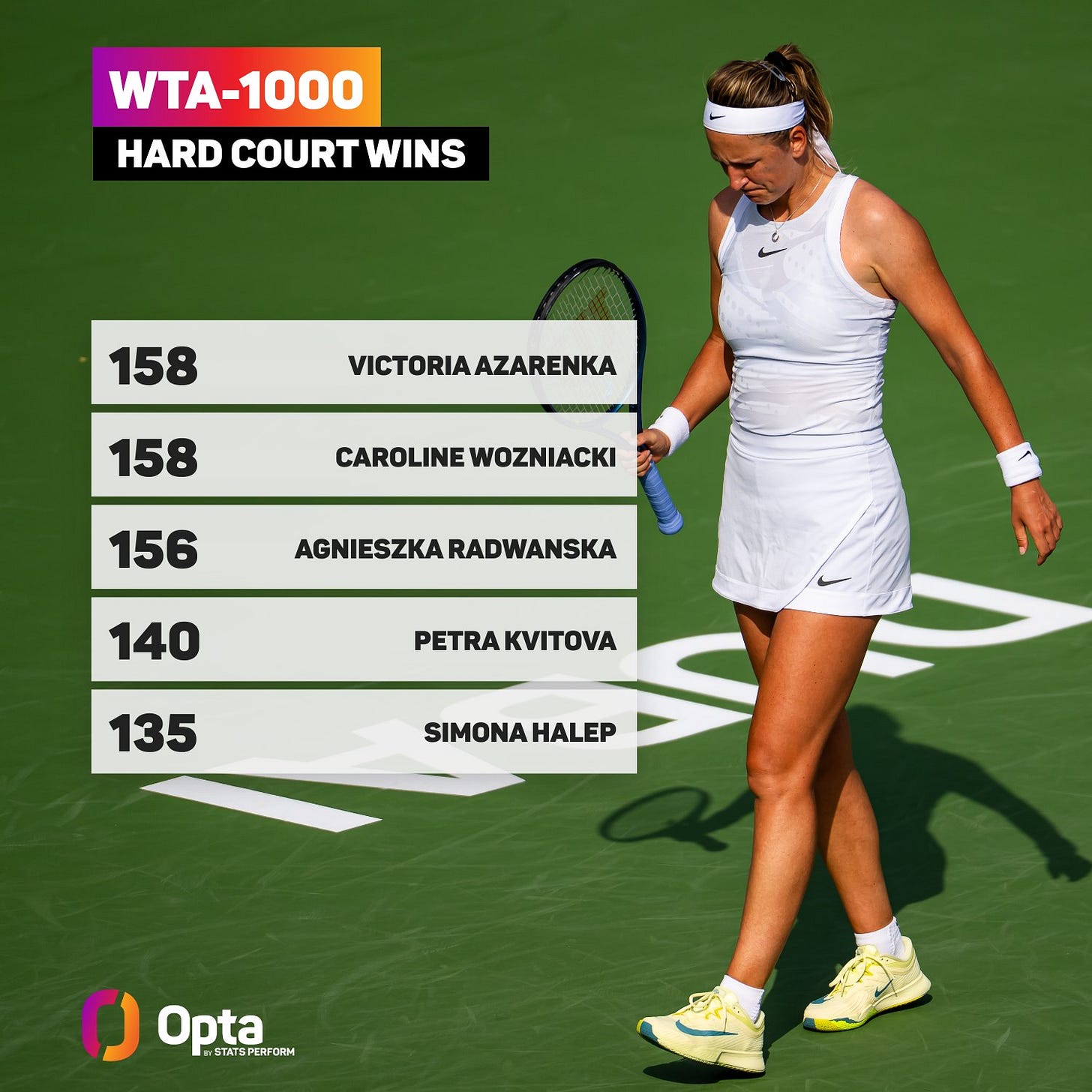

But that incident reflects a deeper concern I have with Opta’s data selectability, particularly in how it classifies event statistics on the WTA Tour. If you follow the account closely, you will see that they often cite WTA 1000 records “since 2009.” The logic behind this cutoff is, presumably, that 2009 marked the restructuring of the WTA calendar, when Tier I events became Premier Mandatory and Premier 5. But the “WTA 1000” branding didn’t exist until 2021, so applying it retroactively to pre-2021 tournaments makes the label a misnomer. If Opta truly wants to respect historical continuity, it could trace back to the original Tier I era (1990–2008) or even the Category 1 events of 1988–1990, rather than arbitrarily starting its count in 2009.

This revisionist framing has real consequences, especially for players whose careers began well before 2009. By limiting “WTA 1000” statistics to post-2009 data, Opta inadvertently downplays their achievements. A recent example illustrates the issue: following Doha this year, Victoria Azarenka (169), Caroline Wozniacki (169), and Agnieszka Radwańska (168) led WTA 1000 hard-court wins ahead of Kvitová (141); that gap would be smaller from Opta’s truncated win tally.

If we follow Opta’s precedent, just imagine what would happen when the WTA inevitably rebrands again. If, say, the Tour renames WTA 1000 events to WTA 999.5 tomorrow, would Mirra Andreeva be hailed as the most decorated player at this level in the future? Would every statistical comparison henceforth require a fresh qualifier, i.e. “since April 2025”?

I do keep my own database as a sanity check for when Opta slips up, but I also credit them for pioneering narrative-driven event statistics, and that’s exactly what I’m aiming to do with @OptaLena: deliver a diverse, creative, and, above all, truthful set of statistics, always grounded in context. I try to avoid sensationalism, even if it likely grabs more attention while distorting the story. Take Rybakina’s 2025 season: both “1–5 vs. Top 15” and “1–5 vs. Top 30” are technically accurate, with the latter painting a more negative status quo, but it should be noted that she hasn’t yet faced anyone ranked 16–30 so far this year.

Context is everything.

Good Guys and Bad Guys

While we are on the topics of tennis analytics and statistics, I’m equally captivated by the broader conversation around the sport, provided it remains kind and thoughtful. Tennis has always been, at its heart, a spectator’s game: watching is a shared experience, less an exercise in solitary analysis than a communal act of interpretation.

That’s not to say subjective insights lack value—there’s undeniable heuristic power in individual perspectives. But it’s in the interplay of viewpoints, where questions collide and converge, that our understanding really deepens. A chorus of voices, each fueled by genuine passion, creates a narrative richness no single lens can achieve alone.

Consider my critique of WTA ruling inconsistencies as I recently took a magnifying glass to the WTA’s rulebook and to the rankings it supposedly governs. Alongside some equally curious friends, we spotted a few cases where a player’s zero-pointer vanished from their tally. A typical exchange went something like:

“Why was Player X’s zero-pointer excluded here?” “Maybe there’s an exception we’re missing?” “Unlikely, look at Player Y’s point breakdown.” “Good catch. Let’s run a quick screening.”

Even when debates grow impassioned, they tend to culminate in greater clarity, mutual respect, and an expanded appreciation for the intricacies of the sport. You almost always walk away having learned something new.

Here’s to enriching your tennis journey, and your life, with the joy of shared curiosity and camaraderie.